When I started at my current company, the mandate I was given by the developers was to help them build things people want. It is something I have heard over and over again from developers throughout my career. And frankly, it’s a goal that the organization and the developers should be aligned on. The business wants products that sell. The thing that most undermines a good development team is when they build something that never gets sold, used, or heard about. But too often, organizations don’t know how to do that.

I am going to spend this post breaking down the problems with “building things people want” that I have run into. I will spend future posts talking about strategies on how to address each of those problems.

People – The Problem of Who

There is no product that can meet all the needs of all groups of people. There are hundreds of different kinds of chocolate bars and candies because they appeal to different people, at different price points, at different times. Today I want a Hershey’s Kiss, tomorrow I want a Lindt Truffle. Different products met the needs of different target markets and demographics. So before you can design your product you have to understand who you are designing it for.

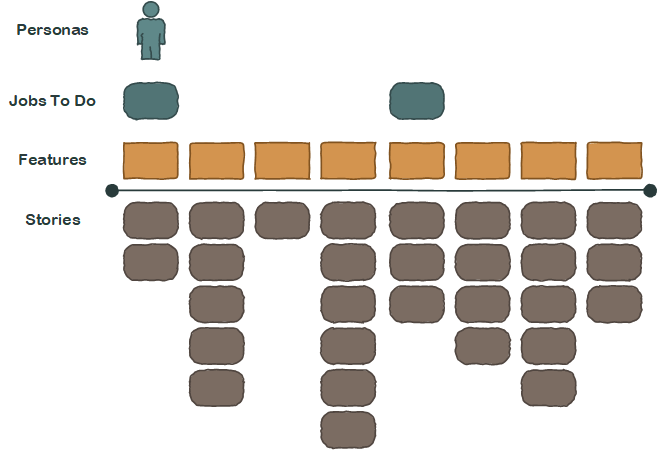

Too often I have seen this turn into a marketing exercise of creating personas. And the persona always turns out to be a woman named Jennifer who is between 25 and 45 and likes walks on the beach at sunset. Personas are great, don’t get me wrong, but I am looking for the problems the persona has that I can solve. I don’t just need to understand demographics, I need to understand what that group is trying to do, why it isn’t working for them right now, and what I can do to resolve those problems. As with most things, I want to start with a problem statement. Then I need to validate the problem statement against real users. Am I solving a real problem? Have I gotten the problem statement right or am I making assumptions to fit the product I want to build?

Okay, now I have a ‘who’ but there is another really important question that goes along with that who: how many of those ‘who’s exist? Am I building a product for one very passionate person? Do I have a robust market segment? Is it a segment I have access to and legitimacy with?

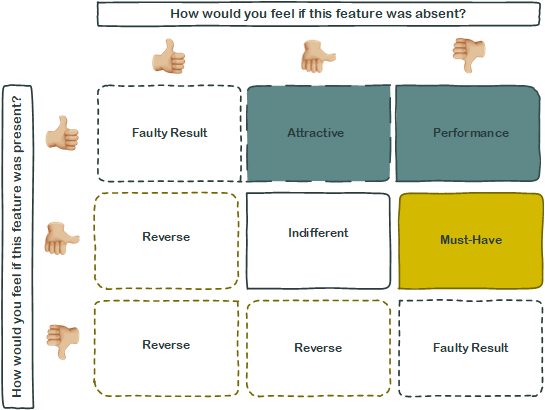

Want? – The Problem of What

Understand the problem statement means I can start to find solutions to help that target market. Here is the truth, though, no organization is capable of solving every problem. Too often companies spread themselves too thin. Just because they find a problem within a target market that they have deep understanding of, access to, and legitimacy with doesn’t mean you have the organizational alignment, focus, and depth to be successful at developing the product, bringing it to market, or supporting it organizationally.

The first set of questions around ‘what’ are questions of product market fit. These are a natural extension of the ‘who’ questions we asked above. How many people want this solution? What is the competitive landscape? Is the market big enough to justify the cost of entry and product development? Can I get enough market share to justify the ongoing cost of sales and support? How are competitors likely to respond? What kind of unique differentiators can I offer? How sustainable and unique are those differentiators? Is my solution better enough than what my potential buyers are using now? What are the switching costs of buyers? What market pressures are their such as buyer power and distribution models?

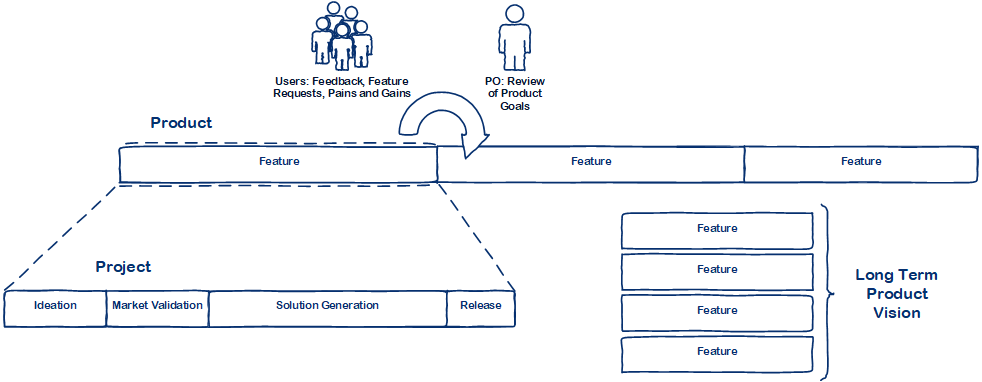

The problem of ‘what’ includes not just what the solution looks like in the initial build and the market, but how this new product fits within your company’s identity. Does this product fit with your long term vision of who you are as a company? Will it support or detract from current offerings? Is it easy to scale with your existing staff? For example, if you been mostly building web applications and now you are going to build a mobile application, what impact does that have on your organizational vision and alignment?

Build Things? – The Problem of How

Let’s say you have something to build that you know people want. Even better than that, it’s something that organizationally fits with who you are. Congratulations, now you are at the problem of ‘how’. We are going to build something, we know who it is for and what we want it to do for ourselves, our clients, and the organization. This is the point where I take off my marketing hat and put on my developer hat.

The first set of questions I have is how we want to organization the development of the product. How much effort? How quickly do we need to get something to market? How thin can our first cut of the solution be in order to start getting feedback? What kind of feedback loops can we build into our development process and what customers can we engage in that process? How will we know when we have something complete enough to release? How do we plan for multiple iterations? How do we communicate timelines and expectations to stakeholders that is a proper balance of managing expectations and giving ourselves room to pivot?

The second set of questions I have is how we approach the product technically. What tech stack are we going to use? How does this fit into or otherwise enable our overall architectural direction? What tech debt should we attempt to address during this process? What unaddressed or unaddressable tech debt do we anticipate facing during this process? Who are the best people for the technical challenges? What information do we need about the system do we need before we start? What is our ubiquitous language? What competitor examples or market concepts can we use as a foundation?

Build things people want seems like such a simple statement on its face. However, it generates a lot of very important business questions for me. In some future posts I will spend some time thinking about different strategies I have used to answer some of those questions.